We will look back on the 1990s as an era of television that was viewed through a smudgey porthole of analogue video technology. This is because television production had shifted from using film as the primary editing-medium to using high-band analogue video tape. This was primarily done to save money, and allowed the use of digitally generated titles and effects, but it has left a legacy of television shows that are trapped within a cage of low-definition video.

To understand this problem, it’s first necessary to look at how television was classically produced. Although video cameras have been around since the 1930s, early video recording technology was of very low quality compared to film technology of the same era. Since techniques (telecine) existed for playing back printed film in real-time as a television signal. This meant that episodic drama was generally filmed, and edited on film for later distribution to local affiliate television stations who would play the film back at the appointed hour through a telecine machine.

Some drama was broadcast live using tube based video cameras. If a repeat was desired a film-camera was pointed at a television to record the episode while it was performed in-front of video cameras (Kinescope). The quality of these Kinescope recording was middling at best. One way around this problem was to use an elaborate video/film camera hybrid called a Electronicam that output a video signal while recording to film for later use during repeats.

Electronicam was used to record the 1950s US TV show ‘The Honeymooners’, and the quality compared to it’s Kinescope recorded rivals is cited as one of the reasons for the shows long-term success.

By the late 1950s Ampex ‘Quad’ video tape was available, and a few shows began to be recorded. Video editing was still not possible, so shows had to be recorded live with carefully synchronized cameras. The high cost of tape of around $300 an hour meant that there was terrible temptation to re-use tape, and this led to the first great video hole.

Large numbers of TV shows were either erased or simply lost as video tape deteriorated.

By the early 1970s a number of solutions to editing video began to emerge, the CMX system along with a number of competitors introduced the concept of controlling multiple VCRs, pulling together an edit decision list, and then compiling the edited piece ‘offline’. These systems were very expensive compared with film-based editors, and were reliant on the reliability and quality of VCRs of the era.

Videotape itself also began taking steps forward with the emergence of Sony Unimatic tape. Which would be followed by the professional version of Betamax, Betacam which would be the backbone of television production in the 1980s.

Videotape Steps Forward

This situation continued until the late 1980s, when it became practically possible to edit on tape. With the workflow in place, a number of other elements dropped into place, in particular cheap video title generation (Quantel paintbox), and later computer special effects driven by products like the Video toaster.

Video camera technology still lagged behind film in many aspects, so for quality reasons, film was still at the front of the capture chain, but then it would be telecined to high-band analogue video, where it could be edited together, titled, merged with effects onto an analogue master tape.

This was fine as far as the producers and consumers were concerned, not editing on film saved time and money, however, instead of a nicely edited inter-postive in the studio vault, there was simply an edited master tape, and a pile of unsorted cans of raw footage.

Two things happened in the 1990s that began to shake things up: The change from 4:3 to 16:9 widescreen as the standard television format and the massive success of the DVD format from 1997 onwards.

License holders of shows that had been in syndication for decades began to get nervous. Just as color television had killed the market for black-and-white re-runs, 16:9 widescreen threatened to kill the market for 4:3 content.

Some shows shot on film began ‘protecting’ for 16:9, and a few shows began to create dual video masters (Buffy the vampire slayer).

DVD Cambrian Explosion

After the market for DVDs exploded in 1998, everyone began looking at what they had in the catalogue that might sell. Generally the masters used for these releases were the same analogue masters used for VHS and Laserdisc production. This didn’t matter that much since early DVDs had a hard time showing all the detail in even these limited masters due to the immature MPEG-2 compression technology.

By 2000 companies were concious of producing too much product, and began to compete on quality, and began looking at creating fresh masters or ‘remastering’ to sell consumers the same thing they’d just bought in higher quality.

Producers of shows that fell into the video hole suddenly realised that they would have to spend a great deal of money to produce a new master, since the analogue master tape they had was not up to the level consumers were begin to demand.

Music

The other great hindrance to DVD releases of Television shows is the failure to acquire music rights for home video release when the programs are first made. Prior to the explosion of the DVD market, home-video was never a large revenue source for program makers, so often they wouldn’t bother to either license or agree a price for licensing the music they used in a home video release. This meant that when it comes time to produce a DVD, the music copyright holder held all the cards in any price negotiation and is free to gouge whatever price they want. This seems to hit 80s and 90s TV particularly hard, as many shows used popular music from the era rather than a recorded score. Post 2000 most TV producers has wised-up to this and pre-agreed home video license fees upfront.

In some situations this lack of music rights has led to either shows being entirely unavailable on DVD (The Wonder Years) due to the cripplingly high cost of both arranging and paying music license fees, or alternatively brutally re-edited with generic muzak (Northern Exposure).

HD Arrives

However with the arrival of high definition, for shows to stay in the perpetual cash-cow that is syndication they would need to provide high definition master. Up-scaling the existing analogue video-tape masters was not going to fly. Older shows with assembled inter-negatives were easy to re-master. Shows like the original Star Trek, The Prisoner, The Twilight Zone look stunning in high definition.

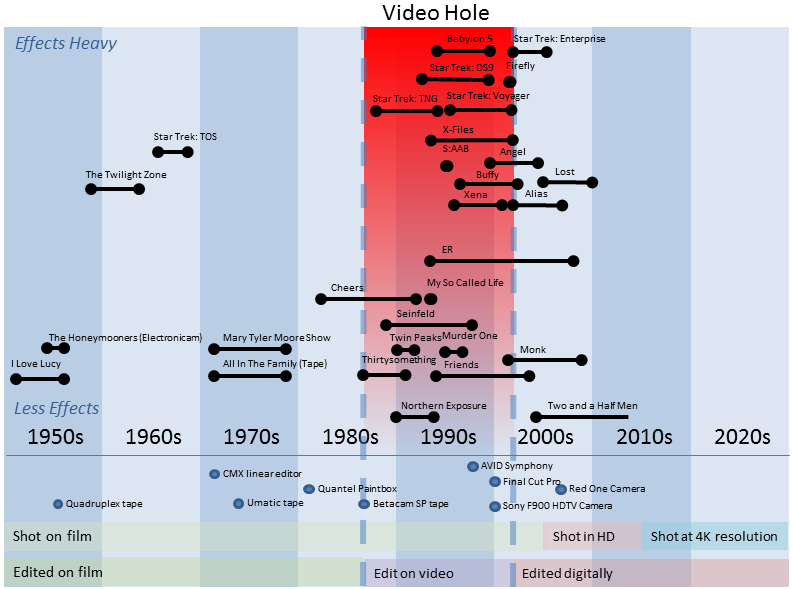

A timeline of television shows, highlighting the 90s video hole. Shows with greater post-production complexity are less likely to escape.

Winners and Losers

However for the shows produced during the video editing era, there was a problem. Though the filmed material mostly exists, it would often be in un-edited negative form. Creating a new master would require basically spending a lot of time assembly, scanning and re-editing the material into an episode, re-creating video titles and special effects.

In general there are three approaches when confronted by this problem:

- Take the hit to protect future syndication revenues. Re-do everything. (Friends, Seinfeld, Star Trek: TNG)

- Do half a job. Rescan all the material, but simply up-scale any shots that contain special effects or titles. (Babylon 5, X-files)

- Give up and hope nobody notices (Buffy The Vampire Slayer)

The significant factor that tends to determine which shows ‘make it’ is how complex it will be to put them back together. For comedy shows like Friends and Seinfeld, there are minimal special effects, so it’s just a case of scanning the negative and re-editing in the digital domain. But for Sci-Fi shows like Star Trek, this may involve re-compositing special effects from source materials which can be almost as expensive as shooting a new TV show. For shows that used a lot of digital effects like the X-files and Babylon 5, this simply isn’t an option, as most of the effects original computer source files have been lost, and the hardware and software needed to render them long since consigned to landfill.

In the case of Babylon 5, the show had numerous challenges. While the human (and alien) drama was shot on film at 24fps with the intent to someday convert it to 16:9, all the effects were rendered 4:3 at 60fps. This gave the special effects a smoothness that made them really jump out. However at the time computer rendering time was expensive, so those extra frames compared to the filmed sections would have nearly tripled rendering costs. If instead, they’d rendered both at 16:9 and 4:3 at 24fps they would have had saved approximately a third of the rendering costs, and be in a much better place to upscale from. Added to which, all of the original data files were ‘lost’ at some point, meaning the effects would have to re-created from scratch.

Buffy The Vampire Slayer has similar problems to Babylon 5, a lot of the special effects are in the analogue video domain. Additionally, the first season was also shot with a back-lit, dark, grainy 16mm film look, that is spot on in terms of tone, but won’t look much better in HD.

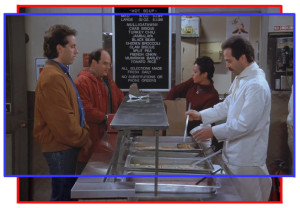

Seinfeld (The Soup Nazi), a later episode of the show. 4 perf 35mm production and loose framing gave plenty of room to recompose in 16:9.

Those that received emergency treatment are a roll-call of television success-stories: Cheers, Friends, ER, Seinfeld and Star Trek: The Next Generation. That list practically defines television I would have set the VCR for in the 90s. These shows are being transplanted to protect future syndication revenues. Typically as part of this process 16:9 HD masters are being produced from 3 or 4 perf 35mm film negatives by scanning the material wider than would have normally been done. From a preservation point of view, this isn’t great, but for studio comedy shoes like Cheers, Seinfeld and Friends, it’s hard to get too excited about, as framing for these multi-camera ‘live’ shows was always pretty loose. For episodic drama like ER, where directors of the week would attempt to impart their style on the piece it is a little more uncomfortable.

Star Trek The Next Generation is a great example of where things are being done right. Since many of the special effects were completed on video, the various component footage has been found, scanned in HD, and then re-composited, while staying true to the original effects. Best of all, the original aspect ratio is preserved. The result is as if a net curtain has been lifted off the television, so that we can see the same actors, effects and drama we always saw, just that bit cleared.

Availability

Many of the shows mentioned below are available in HD on Itunes and other streaming platforms, but not on Blu-ray.

Notable Victims

- Angel

- Babylon 5

- Buffy The Vampire Slayer

- Farscape

- Murder One

- My So Called Life

- Space Above and Beyond

- Xena: Warrior Princess

On The Operating Table

Notable Survivors

- Cheers

- ER

- Friends

- Northen Exposure

- Seinfeld

- Thirty Something

- Star Trek: The Next Generation

FTC Disclosure: I am an iTunes and Amazon affiliate advertiser, this means that if you click on one of the links above, I get a very small amount of money.